Misho Antadze was born in 1993, in Tbilisi, Georgia. He studied Film and Video at CalArts in Los Angeles, where he finished The Many Faces of Comrade Gelovani. After CalArts, he worked as a video editor and a translator, and finished several films. His work has been shown at the Viennale, Ann Arbor Film Festival, L’Age d’Or and others. He makes observational essay films. His research is focused on atmosphere in film.

In the coming weeks we will share updates from the researchers in the master’s programme, as graduation after summer approaches.

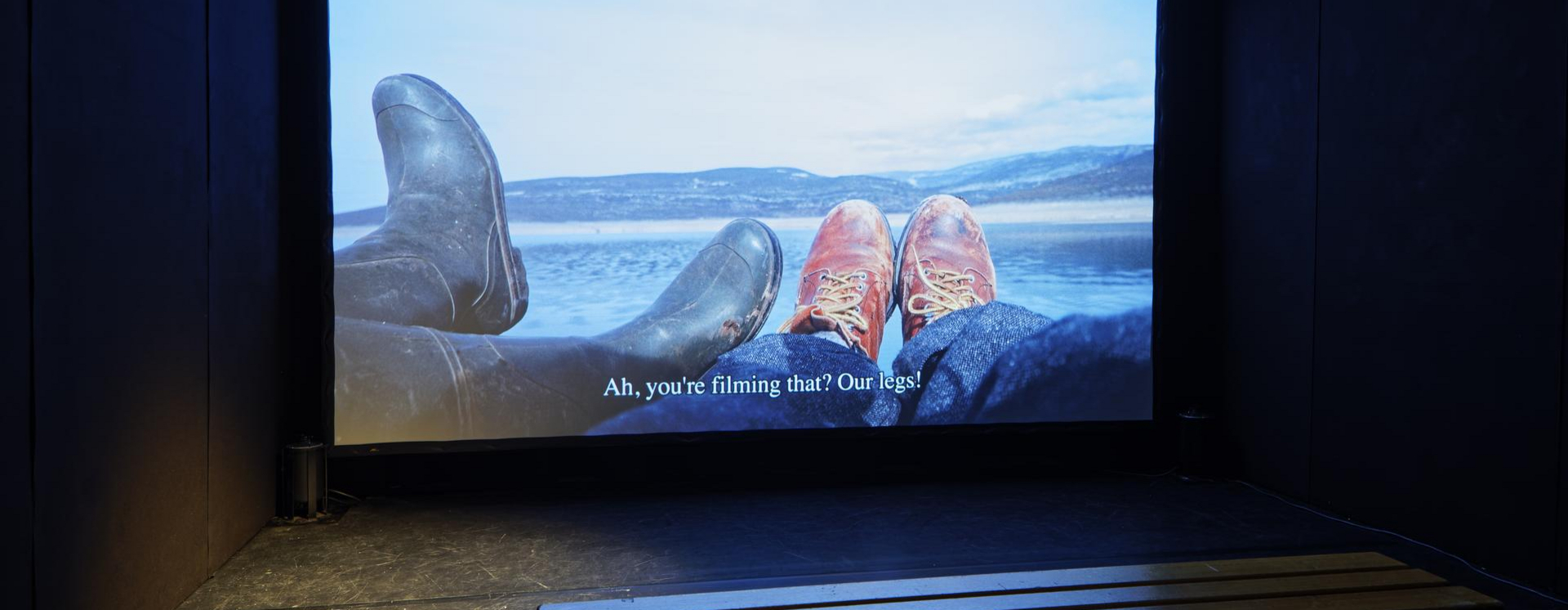

In his research, Misho Antadze explores new ways of relating to history by looking at the ways statues and monuments are intertwined with our collective memory and landscape. During the masters programme, Misho created a film (titled Ozymandias, after the poem by the British Percy Bysshe Shelley) about the monuments and statues honoring Stalin that are placed throughout Georgia, the country where he was born. The idea for his research started in his birthplace Tbilisi, at the Stalin-museum, which Misho describes as “a kind of Stalin DisneyLand”. There however, he realised that the politics intertwined with this place and its presence in the city, didn’t solely belong to the museum. “The politics of memory that are in effect here, are present almost everywhere you go,” Misho adds.

Through Misho’s methodology, he explores how histories are contained or absent from a landscape, from objects, or a situation. How much you can actually find out and how much will remain a mystery, just by looking and listening to your surroundings? “With my research I explore history and how we relate to it, and subsequently find new ways of (re)acting. In this way, we can see how things that we don’t think are still present, actually very much are.”

It is therefore, to say the least, an interesting time for Mishno to finish his research, now all over the world people have torn down statues as part of the protests against racism and the glorification of colonialism. “Statues are not just statues – a fact that is now really being brought to the forefront.” And although the current affairs didn’t change the contents of his research, it did make him feel a different way. Misho adds: “One of the things filmmakers like me, who are not from first world countries, are often confronted with, is this bias that their work is very local, and not relevant to the world at large. Meaning, in this context, always the Western world. In that aspect, what is happening now feels rather cathartic.”

The lockdown did put parts of his project to a halt. Misho was planning on going back to Georgia to re-record the atmospheric sounds in the places he shot, and restage some of the conversations he recorded on location. “I kept a fairly extensive record of overheard conversations, little bits and pieces of things that people mentioned in passing. These will play in the film. You wont get to see who says them, they are more like these ghostly presences coming in and out. Unfortunately I had to postpone this part of my research until I can travel again.”